'Let the fears run through you': What can free solo climbers teach us about overcoming anxiety disorders?

By Anthony Berrick | September 16, 2019

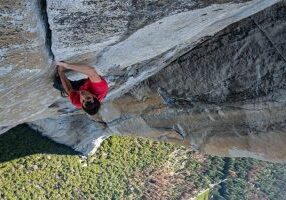

In 2017, Alex Honnold became the first human to ascend the 914-metre-high vertical cliff-face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park without any ropes or safety equipment to prevent him from falling.

This July, 19-year-old George King achieved instant fame by climbing to the top of London’s 310-metre-high skyscraper, known as The Shard – also with no safety equipment.

Alex and George are known as ‘free solo’ climbers. As well as demonstrating incredible physical skill, free soloists require next-level mental skills to enable them to successfully complete hours-long climbs without being crippled by the fear and anxiety that inevitably comes with being just one mistake away from certain death.

While their feats may seem superhuman, if the mental skills that free solo climbers employ could also be developed by us mere mortals, they would be extremely useful for individuals dealing with anxiety disorders such as panic disorder, phobias, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

Introducing psychological flexibility

The ability to make room for difficult internal experiences (i.e. thoughts, feelings, sensations, and urges), and take effective action towards goals and values, is called psychological flexibilty.

Psychological flexibility is the outcome of six core psychological processes (present-moment awareness, self-as-context, acceptance, defusion, values and committed action)1 working together, which can be summarised in the following three steps:

1. Be present: Notice your thoughts, feelings, sensations and urges as they unfold from moment to moment, being aware that you are not your experiences, but the experiencer of them.

2. Open up: Make room for your private experiences, just as they are (not as they say they are), without trying to alter them in any way.

3. Do what matters: Focus your energy and attention on taking action in accordance with your long-term goals and core values.

Greater psychological flexibility is associated with reduced incidence of anxiety disorders, depression and substance use, and better physical health, work performance, and overall quality of life.2

On the other hand, lower levels of psychological flexibility are associated with a higher likelihood of depression, anxiety disorders and eating disorders – even after accounting for an individual's levels of general psychological distress.3

In a sense, free solo climbing is the ultimate expression of psychological flexibility – being able to stay sufficiently focused on the physically-demanding act of climbing, even while experiencing intense feelings of fear and anxiety. But how exactly do free solo climbers do it?

How free solo climbers get flexible

In the Oscar-winning documentary about his history-making climb of El Capitan, Free Solo, Alex Honnold shares these insights into how he deals with fear and anxiety:

You’re not controlling your fear – you’re sort of just trying to step outside of it.

When people talk about trying to suppress your fear – I mean I look at it differently. I try to expand my comfort zone by practising the moves over and over again. I work through the fear until it’s just not scary anymore.

As you can see, opening up to these feelings, as opposed to trying to suppress them, is a key part of how Alex deals with (and eventually overcomes) his fears while climbing.

Similarly, George King, in a TV interview following his climb of the Shard in London, gave this reply when asked about whether he feels fearful while climbing:

Of course there is fear… But you've got to let the fears run through you.

In a recent blog post, Emma Ayling, an outdoor sport climber and climbing instructor, describes her process of getting flexible with fear and anxiety while climbing. She talks about being present with her moment-to-moment experience while climbing:

Being in the moment, being present, focusing your awareness or whatever you like to call it isn’t easy.

I breathe, I listen to my breath and try to focus my attention on that, on the rock under my hands, on the next few moves that will get me to the next bolt and safety. My world becomes very small.

But does she also experience fear when she climbs, and what does she do with these feelings if they show up mid-climb? To find out more, I spoke with Emma and asked her how she deals with feelings of fear and anxiety. She told me:

It’s not that you don’t feel fear, you see it, you acknowledge it and keep moving. You focus your energy on the task at hand.

She describes in more detail, in her blog post, how she focuses her energy and attention on the physical act of climbing:

I play games with myself. ‘Just one more move,’ I say, ‘you’re at your bolt, you’re safe here,’ then when I have climbed up above the bolt and I want to fall even less, ‘just one more move to that good hold,’ or ‘just two more moves and you can clip that next bolt.’

And what happens over time as she repeats this pattern again and again, climb after climb?

The more I do it, the more I push myself and have success, the easier it gets.

So, how does this approach to dealing with fear in a death-defying free solo climb apply to someone with PTSD, OCD, social anxiety, panic disorder, or a phobia, who may be barely able to function in seemingly innocuous everyday situations?

Getting flexible with anxiety disorders

An important point to note, is that there is no qualitative difference between the fear and anxiety someone with an anxiety disorder experiences in the context of their condition, and the intense feelings of fear and anxiety someone else might experience in another context, such as free solo climbing.

Indeed, what makes anxiety 'disordered' in an anxiety disorder is not any unique feature of the anxiety itself, but the impact that the experience of anxiety has on the individual's ability to take effective action towards their values and long-term goals when it shows up.

So, just as the subjective experience of fear and anxiety isn't a problem for free solo climbers as long as they are able to make room for it and focus on the task at hand, with enough psychological flexibility these feelings need not be problematic for someone with an anxiety disorder either.

To put it another way, an anxiety disorder simply ceases to exist if feelings of anxiety no longer get in the way of the individual's ability to do what matters to them and live their life to the fullest.

Therefore, in an anxiety disorder, the problem is not the anxiety itself, but the counter-productive struggle with anxiety that the individual gets caught up in when feelings of anxiety show up.

In acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a person with an anxiety disorder learns how to observe their anxious thoughts, feelings, sensations and urges, without struggling with them, in order to focus their energy and attention on taking action in accordance with their core values and pursuing long-term goals.

While psychological flexibility covers a broad range of human abilities, it is also context-specific. So, in ACT, these skills are developed, practised, and applied, gradually, across numerous different contexts, and with a wide variety of private experiences, until the individual is able to experience strong feelings of fear and anxiety without being significantly functionally impaired.

Over time, just as Alex Honnold and other free solo climbers "work through the fear until it's just not scary anymore", individuals with anxiety disorders also tend to experience significant reductions in fear and anxiety by repeatedly practising the three steps of psychological flexibility in their own fear-inducing situations.

Although free solo climbers may outwardly appear to have very little in common with individuals crippled by anxiety disorders, their approach to dealing with fear and anxiety can be utilised just as effectively in the midst of a panic attack on a crowded train as it can half-way up a 914-metre-high vertical cliff-face.

1. Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

2. Kashdan T., & Rottenberg J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865-878.

3. Levin, M. E., MacLane, C., Daflos, S., Seeley, J., Hayes, S. C., Biglan, A., & Pistorello, J. (2014). Examining psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic process across psychological disorders. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3(3), 155–163.

+61 423 089 645